Getting a jog now and again is a great way to get cardio. Unfortunately, not everybody is built for long-distance running. If you sense persistent knee pain while running, you might have iliotibial band syndrome.

In this article, we will tackle more facts about iliotibial band syndrome, starting with what it is again.

What is Iliotibial Band Syndrome?

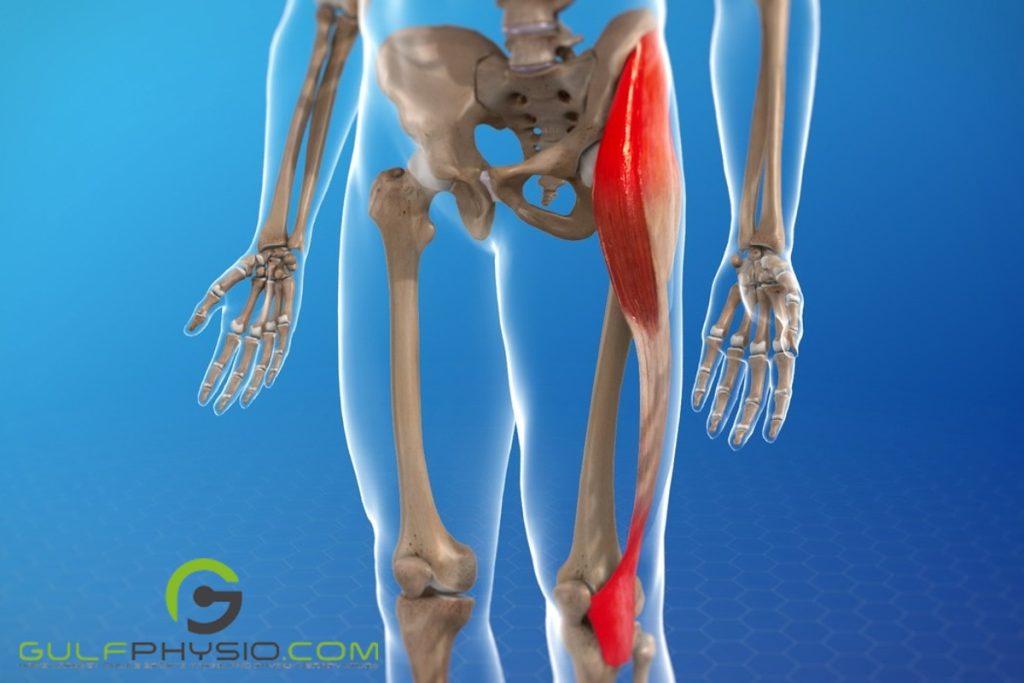

As a recap, iliotibial band syndrome involves the iliotibial band. The iliotibial band is a tendon in your leg that connects your knee to your pelvic bone. As the tendon tenses, it becomes swollen and irritated when it rubs too much on your hip and knee bones.

This condition is fairly common for athletes, particularly for runners and cyclists. It’s a good thing that it’s highly treatable when identified early on. Most people with an injury like this are expected to have a full recovery.

Are There Types of Iliotibial Band Syndrome?

Yes, there are two (2) types of iliotibial band syndrome. Iliotibial band syndrome can occur in one or both knees. If the patient has this condition in both of their legs, then it’s considered bilateral iliotibial band syndrome.

Iliotibial Band Syndrome: Differential Diagnosis

Many athletes have reported pain in the lateral part of their knees. This pain is also evident in their different gait patterns since they can’t bend their knees. The pain can also be seen when replicated in clinical tests.

Nevertheless, this pain doesn’t automatically mean the patient has iliotibial band syndrome. Other differential diagnoses are as follows:

- Biceps femoris tendinopathy

- Degenerative joint disease

- Fracture

- Lateral collateral ligament sprain

- Lateral meniscal tear

- Myofascial pain

- Popliteal tendinopathy

- Referral pain from the lumbar spine, sacroiliac joint, or hip

Tests for Iliotibial Band Syndrome

To rule out iliotibial band syndrome, doctors primarily use two (2) tests: Noble’s compression test and Ober’s test. Ober’s test evaluates the tightness of the iliotibial band in the affected leg. The patient is asked to lie on their unaffected side for this test. Unlike Ober’s test, Noble’s compression test requires the patient to lie on their back.

Another test involves the Trendelenburg sign. If the patient exhibits a positive Trendelenburg sign, the gluteus medius is weak. This indicates compensation for and irritation of the iliotibial band.

Iliotibial Band Syndrome: Etiology

Iliotibial band syndrome frequently presents itself due to defective biomechanics or atypical anatomical aspects. Some of these anatomical factors include:

- Foot and knee alignments

- Iliotibial band tightness

- Lateral femoral epicondyle size

- Q-angle

In terms of biomechanics, a lot of elements can exacerbate it. For instance, some researchers have debated the contribution of the discrepancy in leg lengths. Inequalities in leg lengths, disproportionate foot pronation and excessive force on the genu valgum lead to friction. Too much friction can aggravate the iliotibial band.

Furthermore, gradual and drastic changes in the kinematics of the lower extremities are evident in iliotibial band syndrome patients. These shown below can further worsen your already defective biomechanics:

- Greater femoral external rotation

- Greater peak knee internal rotation

- Greater peak hip abduction

- Poorer muscle performance, like the hip abductors

Anatomic Considerations of ITBS

First Attachment Sites of the ITB

The iliotibial band (ITB) stabilises the lateral part of your knee. It emerges from the superficial fibres of the gluteus maximus. The ITB then carries on at the thicker longitudinal side of the lateral distal deep fascia latae. It starts from the two (2) distal insertion points of the anterior superior iliac spine. This band then reaches itself to the linea aspera of the femur.

The uppermost edge of the distal femur, around the lateral epicondyle, is the first attachment site of the ITB. It acts like a tendon as it fastens with sturdy obliquely oriented fibrous strands. The ITB is over a bed of adipose tissue, which is fully innervated and thoroughly vascular.

Adipose tissue has both myelinated and unmyelinated nerve fibres, with Pacinian corpuscles. The nerve fibres could be the reason for heightened levels of inflammation which leads to pain from excessive compression.

Other Attachment Sites of the ITB

The ITB itself is ligamentous in terms of function and structure. This is evident due to the first and second attachment sites (lateral femoral epicondyle and Gerdy tubercle). When your knees flex, the Gerdy tubercle tenses. As your gait enters the weight acceptance phase, the tibial internal rotation commences.

The other distal attachment sites of the ITB are as follows:

- Biceps femoris

- Lateral patellar retinaculum

- Patella

- Patella tendon

- Vastus lateralis

Together, they form an upside-down U, supporting the knee on either side and in front.

For any of the distal points of attachment, there is no indication of a bursa near them. This shows that the iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS) may be the compression of the tendon and the Pacinian corpuscles. It further indicates that some cases of ITBS are more like an inflammatory condition.

Biomechanics of ITBS

When your knees shift while you run, the ITB moves to the front and back of the lateral femoral epicondyle. In the swing phase, the ITB and tensor fascia latae sustain hip flexion. This happens whenever these two are in front of the greater trochanter.

Your ITB goes over the greater trochanter when your hip broadens for the push-off and stance phase. It then helps maintain knee flexion whenever it goes beyond thirty (30) degrees by pulling over the lateral femoral epicondyle.

Various muscle groups keep the ITB in position while you’re standing in a fixed and upright posture. Your hips are supported by the tensor fascia latae and the gluteus maximus. When your hip stretches, the ITB remains posterior to the greater trochanter. To let the knee continue in extension, the ITB is anterior (or ventral) to the lateral femoral epicondyle.